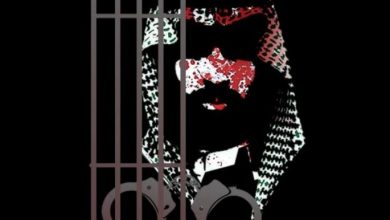

Indications about civil disobedience in Saudi Arabia

Analysts predicted that civil disobedience might erupt in the Kingdom in protest of Bin Salman’s corrupt policies that caused havoc and unrest.

Agence France-Presse revealed that the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice witnessed widespread resignations among employees.

The Agency stated that Faisal, a Saudi teacher, decided to leave his job due to Saudi’s marginalization of the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice.

For years, the Commission, the religious police, enjoyed significant influence and prestige in the Saudi street. Its members closely monitored the application of Islamic Sharia principles in the conservative Kingdom before being practically stripped of their powers in 2016.

“All our powers have been taken away, and we no longer have a clear role at all,” Faisal, a 37-year-old pseudonym, who resigned months ago from the Commission, told AFP.

“Everything I was doing to prevent became completely permissible, so I decided to resign,” the bearded man said in a meeting in eastern Riyadh.

It is worth noting that since bin Salman assumed power in 2017, the Kingdom has undergone social reforms, including allowing women to drive cars, allowing concerts, and ending the ban on mixing between men and women.

“In the past, there was only one body known in Saudi Arabia, which is the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue… Today the most important authority is the Entertainment Authority,” referring to the Entertainment Authority that Saudi Arabia created in May 2016.

On the other hand, Turki, a pseudonym for a former member of the Commission, said that “the commission’s presence has become completely formal.”

“We are no longer allowed to interfere and change any behaviours that we considered inappropriate,” the man in his forties who worked for the authority for more than ten years added, noting that many continue to work “for the sake of salary only.”

In the past, the Commission had great powers, including ensuring that people applied the rules of public morals and the prevention of mixing, which included the right to request their documents and chase and arrest them.

Likewise, the Commission’s cars were roaming the streets. Its members ensured that women were committed to wearing the black abaya exclusively. They pursued the patrons of cafes and commercial centres and forced shops to close during prayer time.

With reducing its role in the street, the authority has finally launched campaigns to raise awareness of morals, confront the epidemic, and warn against instigators of sedition on digital screens, billboards in the streets, and social media platforms.

Hundreds of the Commission’s employees now spend their time in the offices, avoiding interacting with people and raising frustration and anger.

While a Saudi official, who asked not to be named, told AFP: “The commission has become isolated,” referring to “a significant reduction in the number of its members, especially those who are not qualified to call.”

On the other hand, the exact number of its members is currently not known. Still, it is estimated, according to one of the sources, about five thousand in the Kingdom, where more than half of the population is under 35 years old, according to data issued in 2020.

In 2018, the Shura Council, by a large majority, rejected a proposal to merge the authority into the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, citing the need for it to continue to combat drugs.

For his part, Stéphane Lacroix, a professor at the Institute of Political Sciences in Paris, ruled out that Saudi Arabia would move to dissolve the Commission. He said, “The authority remains a sign of a distinct Saudi identity with which many conservative Saudis are associated. What is most likely is the continued re-employment of its role.”