The ‘Biden doctrine’: How not talking to MBS could impact Saudi-US relations

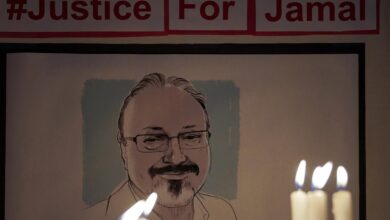

The United States and Saudi Arabia are entering a new era in their 76-year partnership with the release of the CIA assessment finding that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman “approved” the 2018 murder of prominent Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Before now, an American president has never cut off personal links to the Saudi heir apparent, who has often served as de facto ruler of the kingdom. But the White House incumbent declared his intention to make that very heir a “pariah” in Washington and internationally as well.

The State Department has also set a new precedent by issuing visa restrictions on 76 Saudis – three names were later removed – “believed to have been engaged in threatening dissidents overseas” under a new “Khashoggi ban” created in memory of the Saudi journalist brutally murdered and dismembered inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018.

The victim, who had taken up residence in exile outside Washington, D.C., wrote occasional critical commentaries about the crown prince for the Washington Post over the year before his assassination.

A lifetime ‘stigma’

The crown prince, known as MBS, was deliberately spared from the Khashoggi ban, or any other sanction, to preserve a modicum of communication and cooperation between the two governments. Still, as the former Saudi ambassador to Washington, Prince Turki al-Faisal noted, the crown prince is destined to live under a lifetime “stigma” for his role in the affair. He is unlikely to be invited to the White House for years to come.

When the king dies, Biden would presumably refuse to communicate with the new monarch, an unprecedented situation in the history of US-Saudi relations dating back to World War II

Biden has said that from now on, he will only talk to King Salman, Mohammed’s father and the American president’s official counterpart. But the king is 85 years old and in failing health. When he dies, Biden would presumably refuse to communicate with the kingdom’s new monarch, an unprecedented situation in the history of US-Saudi relations dating back to World War II.

In the past, the personal relationship between the US president and the reigning Saudi monarch has been a key determinant in setting both the tone and substance of ties between the two countries. At this point, the only senior US official authorised to talk to Crown Prince Mohammed, who is also minister of defence, is his counterpart, Secretary of Defense General Lloyd Austin III.

It is too early to predict what effect this freeze in communication between leaders will have within the ruling House of Saud on Mohammed’s destined ascent to the throne. The crown prince is said to be very popular among young Saudis, but his ruthless tactics used to grab power from two former crown princes have made him numerous enemies among more senior-ranking princes.

A sharp contrast

The Biden approach to dealing with Saudi rulers stands in sharp contrast to that under former President Donald Trump. He chose to make his first trip abroad to Saudi Arabia where he was treated like a king, and he consulted constantly by phone with the crown prince on the making of US policy towards Iran and a settlement of the Palestinian issue. His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, had a particularly close working relationship with MBS.

Trump bragged with some that he had “saved the ass” of the crown prince from the wrath of Congress. The former president vetoed numerous resolutions calling for a suspension of arms sales to the kingdom and demands to punish the crown prince for ordering Khashoggi’s murder.

FDR meets with Saudi King Abdulaziz ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincy in Feb. 1945

President Franklin D Roosevelt meets with Saudi King Abdulaziz ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincy in February 1945 (Getty images)

What impact the new “Biden doctrine” towards the crown prince will have on the overall US-Saudi relationship remains to be seen. But it seems likely it will be reduced mostly to formal state-to-state transactions and avoid an open break which neither side wants.

The main glue of the relationship remains massive US arms sales to the Saudi kingdom and covert cooperation in combating terrorism. Since 2010, the US Defense Security Cooperation Agency has notified Congress of $134bn in potential arms sales to Saudi Arabia, which has been the most important foreign market for the American defence industry for decades.

The Biden administration has reiterated its commitment to defending Saudi Arabia from foreign aggression and will continue to provide “defensive” arms. However, it has already announced the suspension of “offensive” weapons in use against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels who have seized control of most of neighbouring Yemen. Forthcoming arms sales to the kingdom are now under review, presumably to determine which are defensive and which offensive.

Saudi Arabia’s main military challenge right now is shooting down scores of Houthi drones and missiles fired regularly across its border. Earlier this month, a Houthi drone hit an airport in southwest Saudi Arabia, puncturing a hole in an Airbus A320 civilian aircraft.

The Iran factor

Other than the crown prince, the most divisive and immediate issue in US-Saudi relations is how to deal with Iran, the kingdom’s arch-rival for regional primacy. Iran has proven itself to be the most serious military threat after demonstrating its ability to amass drones and cruise missiles to knock out nearly half of the kingdom’s oil production for several weeks in September 2019.

Biden’s about-face toward Iran from Trump’s hardline stand seems certain to lead to even more discord in the fraught US-Saudi relationship

Biden has begun charting a diplomacy initiative to entice Iran back into the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) aimed at preventing it from developing nuclear weapons. Former President Trump regarded the accord as the “worst ever” in US diplomatic history and withdrew the United States in 2018.

Saudi Arabia applauded Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign of economic and financial sanctions to force Iran to renegotiate the accord with added constraints on its expansionist activities in neighbouring Arab counties. However, Iran made no concessions and slowly broke, one by one, many of its JCPOA commitments.

Biden’s about-face toward Iran from Trump’s hardline stand seems certain to lead to even more discord in the fraught US-Saudi relationship – one no longer buttressed by all-important personal ties bonding US and Saudi leaders in the past.

This commentary was first published by the Middle East Program of the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C.